Caring for people with Alzheimer's disease. Advances and challenges.

On the occasion of World Alzheimer's Day, we thought it would be interesting to review some of the most relevant aspects of a disease that affects around 43 million people in the world, 85% of whom are over 75 years of age. According to the existing evidence, we know that its incidence doubles every decade from the age of 60 onwards, something we are already witnessing in residential centres, where almost two thirds of the people living there have cognitive impairment or dementia.

Furthermore, different community studies suggest that 35% of Alzheimer's cases are due to modifiable factors, especially at older ages and closely linked to the main determinants of health, such as aspects related to lifestyles (physical inactivity, obesity, smoking...) and socio-economic level (educational level, social interaction...), among others.

With this demographic reality, geriatric assessment tools acquire great relevance when it comes to detecting the different needs present in the physical, psychological/behavioural, functional and social domains, facilitating the comprehensive approach that all these people require.

Alzheimer and its progress

To speak of Alzheimer's is to speak of a progressive, unstoppable and irreversible disease that affects the most precious part of people: their cognitive capacity.

Although in the beginning it may be due to absent-mindedness and carelessness on the part of the person, its evolution leads to the loss of the ability to retain recent events and the progressive forgetfulness of one's own biography. The person may stop recognising loved ones, have delusions and, in many cases, become aggressive and irritable. Another common feature is the loss of spatio-temporal orientation. Thus, the person may want to go for a walk in the middle of the night, thinking that it is daytime, or get lost in familiar spaces, including their home.

All of this has an impact on good judgement and the ability to make coherent day-to-day decisions. The person starts to need support to manage their money, control their medication or manage their own hygiene.

In addition to this, there are situations of incontinence, worsening mobility accompanied by an increased risk of falls and associated injuries, difficulties in eating and drinking, leaving the person at the mercy of malnutrition, pressure ulcers and recurrent infections.

In advanced stages the person loses the ability to communicate. They cannot express what is happening to them, nor can they ask for help with their most basic needs: cold, hunger, thirst, pain, anxiety, urination, changes in posture, company, affection or closeness. Although she is still herself, part of her seems to have gone.

Alzheimer's and its current approach

Alzheimer's dementia is one of the most studied diseases in the history of medicine, with many processes involved in neurodegeneration being understood and unravelled. Although current therapies, from tacrine to aducanumab, slow down cognitive impairment somewhat, they all show little effect on behavioural or functional aspects, so caregiver overload persists.

What should care be like for a person who needs support to plan their future, who does not enjoy the freedom and independence they once did, who misinterprets reality?

While we wait for science to advance, good care should be underpinned by ethical considerations, recognising the dignity of the person, their finitude and what is important to them.

The main goals of care are to minimise functional impairment and once disability and dependency appear, the search for the highest possible quality of life, as well as the prevention of caregiver overload. But how can we measure this in a person in the situation described above?

Perhaps the answer lies in what we call "comfort" (absence of pain, no dyspnoea, no psychological discomfort) subject to aspects such as respectful treatment, closeness and the accompaniment of loved ones, as well as having staff trained in care centred on the person's own interests. In line with the above, the use of scales such as LIBE (List of Indicators of Well-being), an instrument created to determine the well-being of people with dementia, and thus be able to assess the impact on them of both the environment in which they live and the practices that are generated around them, should be recommended.

As it greatly affects older people with various pathologies, the objectives of their control must be in accordance with their cognitive and functional situation, so the levels of control of blood pressure, glycaemia or other variables must be more conservative, due to the inherent risk of falls, functional deterioration or confusional pictures that this entails.

Prevention of induced immobility should be approached with regular and adapted exercise, as well as psychostimulation (reminiscence techniques, music or aromatherapy), interventions that slow down part of the deterioration process.

In those cases that, due to the evolution of dementia, are in advanced stages or with a short life expectancy, advanced end-of-life planning shared with the main caregiver protects the person and informs those accompanying him/her about the real prognosis of the disease, identifying the interventions and care resources that are most proportional to the needs detected, avoiding futile diagnostic tests or interventions that do not add value, and especially a therapeutic adaptation that avoids polypharmacy, continuously carrying out a proportional balance of benefits and risks.

Over the course of time, the possibility of maintaining or not the driving licence must be assessed, in a progressive process of capacity loss.

There are many people who have made their living will on the attitude and measures to be taken by healthcare professionals and society as a whole when they reach certain degrees of deterioration, requesting euthanasia as the last decision of their freedom, as disability and dependence entail intolerable suffering for them. The various existing ethical dilemmas, and those that will emerge with the social and cultural changes in society, require prudent deliberation.

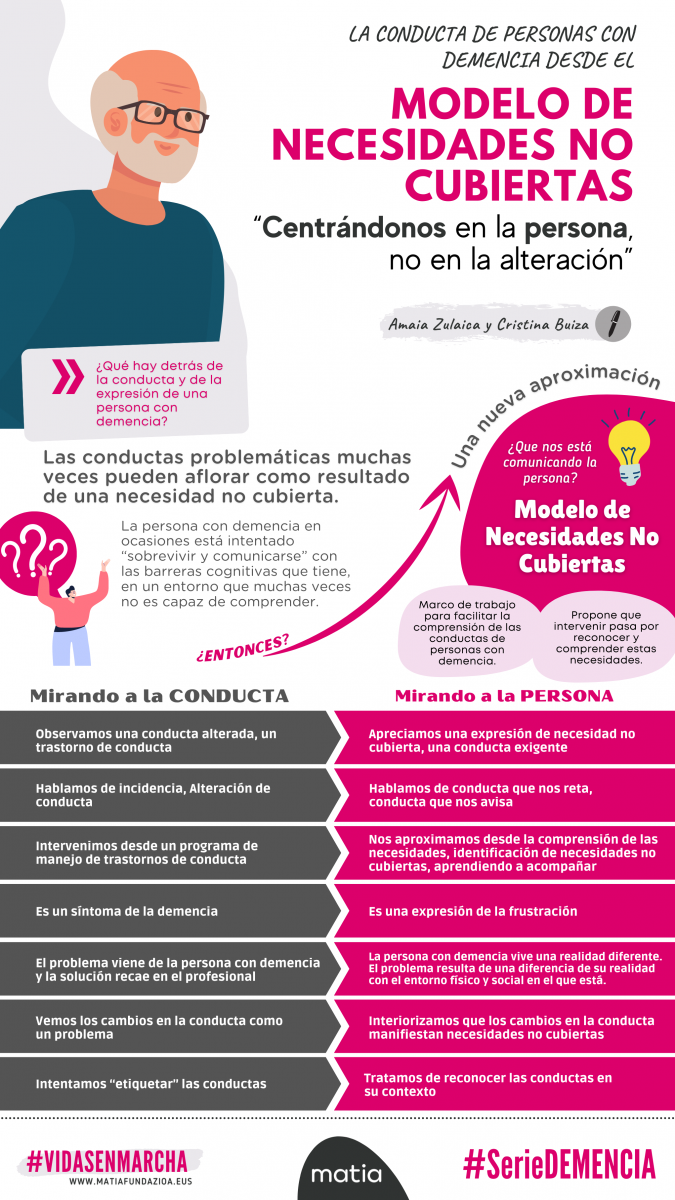

Focusing on the person not the disorder

Behavioural disturbances (anxiety, depression, hallucinations, delusions, sleep disturbances) make coexistence very difficult and worsen the prognosis. Their approach must be multicomponent, from a focus on unmet needs and identifying the main symptom, establishing care objectives and carrying out pharmacological and environmental interventions, with follow-up over time.

From a new approach to this phenomenon, we can observe that problematic or demanding behaviours are an expression of frustration that emerges as a result of unmet needs that the person, due to cognitive barriers and the physical and social context, is not able to understand and communicate. For this reason, the education of caregivers is essential for their proper management, promoting a culture of care that is capable of providing coping techniques and skills for caregivers and security for people with dementia.

Infografía que recoge los principales elementos del modelo de necesidades de cubiertas

Lessons for the future

Following the COVID 19 pandemic, in which 70% of attributable mortality affected long-term units and geriatric patients, with a major impact on people with dementia, the importance of adequate social and healthcare coverage to guarantee adequate healthcare (control and monitoring of chronic pathologies, geriatric syndromes, pharmacological adaptation) has been highlighted, social (strengthening the figure of the personal assistant to facilitate permanence at home, advancing in the transformation of the model of day centres and residential centres) and community (taking steps in the coordination of the resources present in the ecosystem), so that in the event of decompensation, the most appropriate resource can be assessed early on, avoiding ageism or discrimination due to disability or cohabitation resource.

A significant advance in addressing dementia would be to shift the focus from the disease itself to the person and their family. Knowing their life history, values and preferences; encouraging meaningful activities; putting the individual and their needs at the centre of attention, rather than a culture of prognosis or risk that limits quality of life.

To this end, it is essential that social resources tend to be designed as domestic, recognisable, familiar spaces, like small cohabitation units, which allow for interaction and appropriate environments, and in which all possible pleasurable activities are encouraged, respecting the particularities of each person.

Another aspect that should not be neglected is that of raising awareness of Alzheimer's disease. Society needs information and testimonies from experts and those affected in order to encourage early detection and a comprehensive and integrated approach to this disease, as well as a narrative free of stereotypes which, from a good treatment approach, allows progress to be made in the support and visibility of these people and those who accompany them.

Finally, we should point out another possible ally that arises from the advances of our increasingly digital societies. Technological aids offer us opportunities in areas such as the safety of care, such as the use of telecare in the home, pill dispensers that minimise errors in the administration or preparation of medicines, home meal services or fall detectors.

We cannot conclude without a reflection. As the WHO says, a society is measured by the way it cares for its elderly citizens, especially the most vulnerable. Recent experiences invite us to redouble our efforts to improve the present social contract of care, which is clearly far from guaranteeing the good old age that we all want and deserve to enjoy. Let's get moving.

Add new comment