Reframing dementia

I came across Robin Hammond’s photographs on Instagram. It was the extraordinary, earthy beauty of the portraits that first drew me to them. Every face captured in his lens is old. And you know, even as you take in the wisdom of their eyes or the dignified curve of their nose, that everyone has a story to tell.

Each person, it turns out, has dementia. Swipe right and you discover an object that means something to them: a saw, a book of poems, an agricultural implement. Beside every portrait is a short commentary on the individual’s life, his or her story.

Take 83-year-old Shiwa Sawano (left). She lives in a group home on Japan’s northernmost island of Hokkaido. When she first arrived she used a stick to walk and hardly ever smiled. But now she laughs, smiles and keeps herself busy.

“I am happiest when I’m working in the field,” she says. “Because I grew up in a farm. Work is fun. I like to work”.

Some 36 people with dementia live in group homes in the Sapporo and Eniwa areas of Hokkaido. Food and general care are provided, but residents are encouraged to maintain the routines of daily life, whether that be through gardening, preparing meals, food shopping or cleaning. Some gain a sense of financial independence by selling vegetables that they have grown.

Fira Sawaro watering her garden. Photography: Robin Hammond.

Fumiko Ito was just 19 when she met her future husband in a bar. “He was sitting behind me and he pushed me from behind and said hi – I fell in love at first sight”.

The two of them ran a restaurant for 30 years and then, seven years ago, her husband died of cancer and Fumiko’s health declined. However since she’s moved into the Eniwa group home for those with dementia her condition has improved; she says this is because she no longer feels lonely, she has friends around her and she has a role to play. She prepares food, cleans house, sometimes take care of the other guests and is at her happiest when enjoying good food with friends.

The small, group care homes form part of Japan’s pioneering Orange dementia programme launched in 2015 to provide more specialists, improve early diagnosis and expand community-based care. Japan, which has the oldest population in the world (36 million of its citizens are 65 or over), is living through its third era of dementia. The first, the era of the cure, occurred in the 1980s, when those with the condition were placed in care homes and given medication.

The second, the era of care, came in the ‘90s, when people lived their lives supported by others. Though laudable in its aims, the pioneering treatments of this era – music, reminiscence and art therapies – were foisted on care homes without any thought being given to what their residents might actually want.

The third phase is known as the era of reciprocity: people are regarded not as care givers and care receivers but as treasured partners. In Japan today, 5 million people live with dementia. Emphasis is placed on everyone sharing their lives, on those with and without dementia influencing and being influenced, inspiring and being inspired. The approach is not one way or unilateral, but equal.

I discovered all this through Karin Diamond’s excellent Churchill Fellowship film report about her trip to Japan. She mentions the small, group homes where staff ensure that they know the history of each individual resident by visiting places of significance to them in their earlier life. Her accounts tell of the ebb and flow between residents and staff.

“Humanity is fostered in the warmth of interpersonal relationships” she says.

Karin is the artistic director of Re-Live, an award-winning charity based in Cardiff that provides an inspirational programme of life story theatre work and training courses for those with, and involved with, dementia, for veterans with post-traumatic stress and people with terminal illnesses. One of its missions is to “Create theatre that challenges stigma and changes the way we see each other”.

Which brings me back to Robin. The 45-year-old describes himself as a photo-journalist and storyteller. For a decade he has focussed on mental health, disabilities and human rights, always trying to connect to the issue through the person, to gain what he calls a “person-centred understanding”. Take a look at his website onedayinmyworld.com or his Instagram account to see some of his projects and more of his incredible photographs.

When the Guardian commissioned him to provide images for a story on dementia he travelled to Japan and admits that initially he saw the condition rather than the person.

“But through their conversations I started to see the people. I realised that they had rich histories just like you and me”.

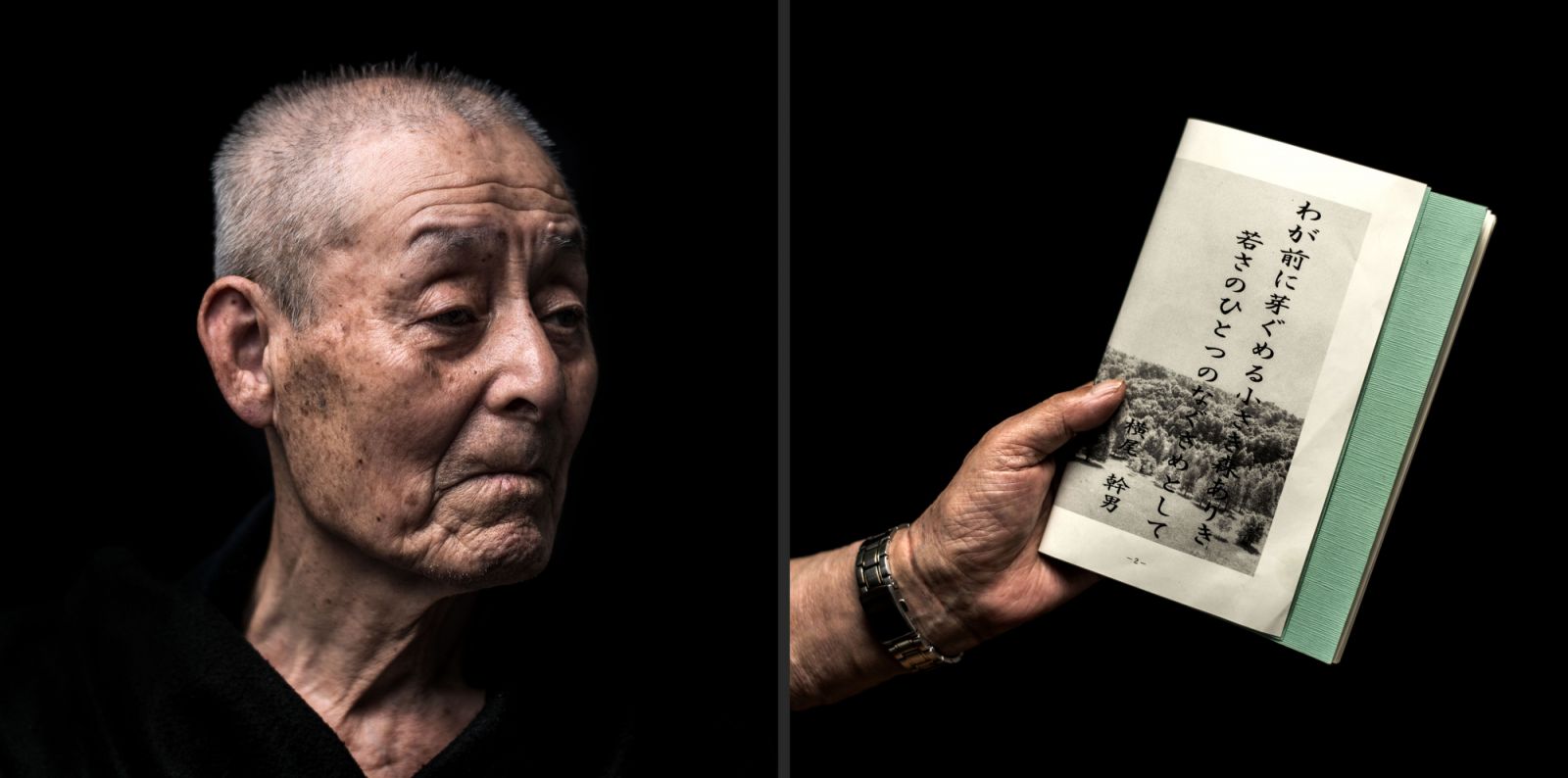

Throughout his life 81-year-old Yoko Mikio wrote poetry but then his dementia made it too difficult. “There is a small forest blooming in front of me,” reads one of his poems, “as one of the ways my youthfulness is soothed”. His wife Ryoko explains that when he was younger Mikio expressed his frustration with life through poetry, which comforted him.

Mikio still thinks he is at work maintaining the Japanese railways even though he retired 35 years ago. Nowadays he always carries a book of poems in which one of his was published.

Retrato de Yoko Mikio (Izquierda). Libro de poemas (derecha). Fotografía: Robin Hammond.

"“When I see the forest and I see the trees moving by the wind I feel the energy of nature, then I feel I also have to do something other than just sitting here all day” he says.

Original text published in Pippa Kellys' blog. Photos courtesy of Robin Hammond.

Add new comment